By Jim Colton

“Experience is not what happens to a man; it is what a man does with what happens to him.” ― Aldous Huxley

Earlier this summer, at the University Photographer’s Association of America Symposium 2015 in Michigan, I had the great honor of sharing the stage with three of my comrades that I have worked with during my tenure as a photo editor; David Burnett, David Hume Kennerly and Joe McNally.

The Four Amigos: Kennerly, McNally, Burnett, Colton. © 2015 Roger Hart

After reading everyone’s bios, and doing some quick math, I realized that between just the four of us, we collectively had about 200 years of experience in the business. It was official. We were ROOFies! (Royal Order of Old Farts) The fact that all of us were there to share our knowledge with a photographic community that was eager to learn was both heartwarming and deeply satisfying. And I am proud to be a ROOFie and would share the trenches with these guys…anywhere...any time.

Last weekend, I conducted two “breakout sessions” on photo ethics and photo editing for students at North Carolina State University. Staring into the crowded room of mostly teenagers, I mentioned that in two weeks, I was going to be attending my 25th consecutive Eddie Adams Workshop. I asked, “Has anyone ever heard of the workshop?” Crickets. I then asked, “Has anyone ever heard of Eddie Adams?” More crickets. Finally, mock-pointing a gun to my head, I made a reference to Eddie’s Pulitzer Prize winning image of the execution in Saigon…and finally, I saw some light bulbs go off. As I age, I am constantly reminded that institutional history is worth preserving.

David Burnett

But as my opening quote infers, it is not just what happens to you but rather what you do with what happens. And if you are very lucky...and very good…you can have a thriving and satisfying extended career by making the most of those life experiences. One of those people, who has carved out a masterful career and continues to do so, is David Burnett.

Burnett’s images have graced the pages and covers of newspapers and magazines in every decade since the 1960’s. He’s won innumerable photo awards including the prestigious World Press Photo of the Year in 1980, an organization for which he has also served as a juror…three times….twice as jury chair! His photographs have been exhibited in museums and festivals from New York to Sydney.

He is the co-founder of Contact Press Images, is the author of several books and was once named one of the “100 Most Important People in Photography,” by American Photo. He’s taught workshops all over the world and has one coming up at the end of this month in Paris, France. (See link below)

Burnett also writes an informative and often hilarious blog aptly titled: “We’re Just Sayin” (See link below) which he touts as containing: “….biting social issues, less biting social issues, social issues with absolutely no bite: all will be treated equally unfairly.” This week, zPhotoJournal has a conversation with a man I am proud to call my friend, co-worker, and photographer…who has more creative staying power than the Energizer Bunny; David Burnett.

Jim Colton: Tell us a little about the early years. When did you first get interested in photography? Who or what were your earliest influences?

David Burnett: I think like almost everyone of my generation, which is to say discovering photography in the 1960’s, I came about it rather by chance when I applied for a position on the Olympus High School yearbook in Salt Lake City. The choices offered were to be on the business staff, the art staff, the literary staff, or the photo staff, and by a process of elimination, since none of the first three appealed to me in even the slightest way I thought I would see what the photo staff was all about.

And like many of that generation who became exposed to photography in the darkroom, I was transfixed by the wonder of watching an 8 by 10 sheet of Kodabromide paper come to life in the Dektol after it has been exposed in the enlarger. There was some kind of magic about that cone of light in the otherwise dark room projecting a negative image on a piece of white shiny paper. Once you had figured out what it meant, and frankly that didn't take very long, you knew that something magical was afoot.

David Burnett at Shutterbug Camera shop: Salt Lake City circa 1965. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

Along with the yearbook, I very quickly started shooting pictures for local weekly newspapers at $3 to $5 a picture and in the era of penny-a-frame for bulk loaded Tri-x, it was, if not a ticket to riches, certainly a lovely and fun way to make a few dollars every weekend. I even became, at the age of 17, the unofficial track photographer for the Bonneville Raceway drag strip and would shoot pictures of the cars on Saturday, spend the week developing the film and making 8 by 10 prints, and go back the next Saturday and sell the prints to the drivers for a dollar each. I made 20 to 30 bucks a weekend which was a lot of money in 1964 (note: a Nikon F body was $220 then) and the drivers got a pretty good picture of their car, very reasonably priced. That was before I understood the concept of space rate.

Like most of my colleagues I never really studied photography other than learning it by making mistakes and because of that I think my technical prowess was marginal in the area of artificial lighting, strobes in particular. I have remained pretty much an available light photographer and I've never really had a complaint about that. I consider it a positive experience if, when a job is over, I can put my strobes back in the car having never opened the case.

JC: How did you wind up in Vietnam? How long were you there?

Burnett's first TIME cover August 2, 1971. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

DB: I had a summer job with TIME magazine in 1967, between my junior and senior year at Colorado College. I had eleven photographs published in the magazine that summer, and realized that in fact I really wanted to be a magazine photographer. Seeing things with my cameras was a great way to get to see the world. I worked after graduation in the Washington and Miami bureaus of TIME, but it was the summer of 1970, there wasn't a lot of work being done by the bureau. Consequently things were pretty slow for me.

Later that summer, when my friend John Olson a young LIFE magazine photographer came back from Saigon and told me that there was still a lot of work for freelancers in Vietnam, I decided to go where the story was. I left in early October, bought a one -way ticket to Saigon, and thought I would go for at least a few weeks and see what developed. I ended up staying two years, had my first serious stories — including my first TIME cover on Pakistani refugees in India — and the last year there, joined LIFE (the weekly) on what would turn out to be the last year of its publication.

JC: You worked with some pretty amazing photographers there including David Hume Kennerly, Eddie Adams and Nick Ut among others. Looking back, what was that like compared to more recent conflicts....including analog v digital?

DB: Dave Kennerly was someone I had met in Washington briefly the year before, and when he arrived for UPI in the spring of 1971, we got back together and became fast friends and while we didn't spend that much time in the field together, we hung out in Saigon, and compared a lot of notes. As it happened, I was with that small group of journalists who had been on the outskirts of Saigon at the village of Trang Bang the day that Nick Ut took his famous picture of Kim Phuc.

Trang Bang, Vietnam, June 8, 1972: 9-year-old Kim Phuc runs naked in the street after a napalm attack. One of David Burnett's images from that fateful day is included in the gallery. © Nick Ut/AP

As I had been working for The New York Times that day I went back to the AP to process my film and send pictures to New York. (Try and explain that process to an Instagram shooter who knows only an iPhone.) I was in the dark room that afternoon when the very first picture - a wet 5x7 print - came out of Nick’s image of Kim Phuc and her family running up the road. It was something to be one of the first people to see that picture, and I did what I suspect any other photographer would do: I looked at it, and tried to figure out if I had something better. (Clearly I didn’t.)

I knew that picture was special, and went back to my Time-Life office to alert LIFE that “there is a very good picture from Trang Bang, and the AP will have the negative in NY in two days.” (One of my pictures ran next to Nick’s the following week in LIFE.) But it was impossible at that moment to know that within a couple of days, hundreds of millions of eyes would see and react to that picture.

Transmitting pictures has changed and the speed of presenting and viewing pictures has increased so much I think it changes the way we look at pictures. It's almost as if we don't have enough time to look at something because we have to rush off to the next image. But certainly pictures by Daniel Berehulak and John Moore (two who come to mind) from the Ebola epidemic last year in West Africa are those kinds of pictures. They almost force you to stop and look, and in a way they demand to be seen. They will not go away quickly.

December 1971: On maneuvers with American soldiers of the 1/7 Battalion of the 1st Air Cavalry, near Xuan Loc, Vietnam. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

Digital of course speeds up the delivery and presentation of the pictures and generally speaking because there are more and more images that aim for our attention it becomes harder for a good picture to be seen and rise above the average. It would be nice if we could all just slow down a little, and look, ponder, reflect, but I fear that isn’t going to happen.

I use digital cameras, and I use some film cameras, but there's no question that there is a certain ease of use which the digital cameras give you. At the same time I am attracted to the more traditional kind of cameras. The mere fact that you can hold a piece of film or a roll of film in your hand and look at it, still to me has a great deal of value. We live in a time of hybrids, and for me, when possible I like to carry the Speed Graphic along on almost all the jobs I do. It forces me to see things differently, and taking into account the difficulties which accompany a big camera (lack of stealth, slow operation, remembering to do all the right things in a particular order) that kind of painting yourself into a corner can have some advantages. You see things you might have missed. I suppose there might be a parallel with the “slow food” movement. You get out of it what you put into it, and if you take the time to do so, something good can come from it.

JC: As a Contact Press Images photographer, you've covered breaking news the world over. What were some of your favorite assignments? And, in the interest of fair play, what were some of your least favorite?

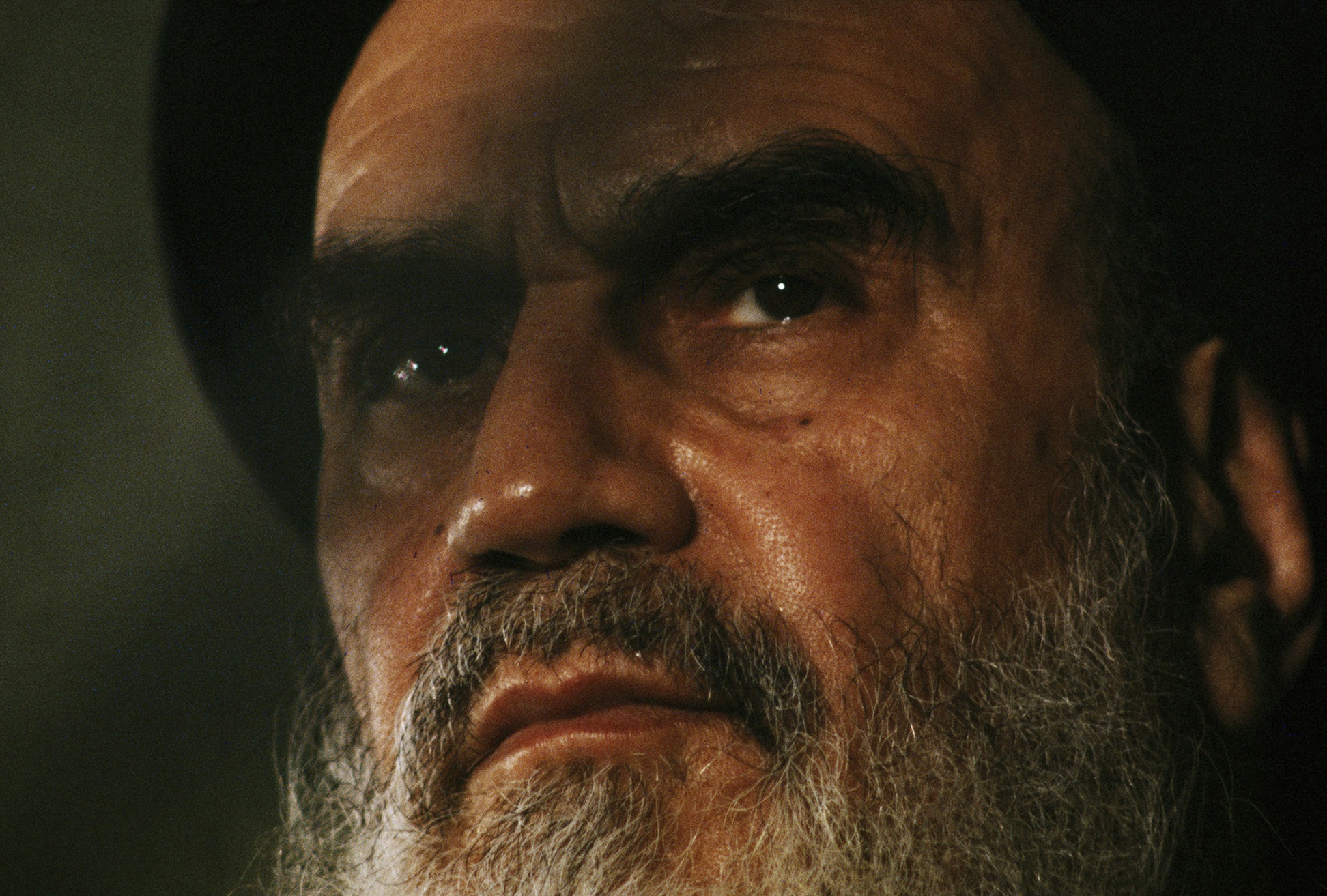

The blood of the latest “martyr” — near the University. Tehran, January 31, 1979. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

DB: I started Contact Press Images with Bob Pledge in 1975, though we didn't really call it Contact until early 1976. We had been working together at the French agency, Gamma for 2 years and while I very much enjoyed the time working together and being with some very top notch photographers - -Raymond Depardon, and Sebastiao Salgado among them - - we figured that if there were going to be issues and mistakes with how the agency gets run, perhaps we could make our own mistakes instead of relying on somebody 3000 miles away. So we started our own agency in a little office on 39th street in what turned out to be the beginning of the last heyday of the magazine world, and off we went. It is hard for me to believe that it's been 40 years; unbelievable really.

You can't imagine how quickly your life flies by. I've had the good fortune to be able to work with some great editors and magazines along the way and some of the stories are things you almost can't imagine being asked to do nowadays. In 1978 I went with a writer down to very rural Brazil to do a story on a Spanish priest who was one of the vanguards of the liberation theology movement for the then newly published GEO Magazine. We spent 2 weeks with the good Father then went back to Rio, and the writer went home, confident that he had his story. But I felt that I needed a little more time and I called the photo editor — the great photographer Thomas Hoepker who was then the photo editor at GEO. He was wonderful. He said take a week in Rio, give the man a rest, and then go back for another week, which is exactly what I did. And it was on that second trip where I just popped back into the priest’s life, without an intrusive writer next to me, that I was able to make most of my good pictures.

Ayatollah Khomeini is served tea in his room at the Refah School by Sadegh Khalkhali, who later became known as “the hanging judge.” Tehran, February 5, 1979. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

Other than GEO or National Geographic I can't even think of anyone in today's world who would happily send you off for a month on an assignment for a story that might run 15 or 20 pages. These days if you get a week on an assigned project you're doing above average. I've been lucky to get assignments that I think force me to reach a little bit beyond what I am comfortable doing, and I think for all of us there's something to be said about leaving your comfort zone now and then, and trying to attack something on a whole new level.

Frankly that's one of the reasons that I've been trying to shoot with my old 4x5 camera — because I am not terribly skilled at it, but at the same time it's something that I feel in the right circumstance, to make a picture that has a different feel or a different look than I might do with my digital cameras. And sometimes just making it harder for yourself is the key to finding a picture that you didn't know you had inside you.

As far as most favorite and least favorite stories sometimes it's the same story. I have to say that there were times when late at night cleaning my cameras, listening on my little short wave radio to BBC World Service to try and get a bead on what was happening in the world, getting all the film sorted out, I would look around in some crummy little motel room and think “What the Hell am I doing here?” But even on the lousy assignments you can make a good picture and that's something I think is worth remembering.

JC: You worked closely with photographer Olivier Rebbot in Iran. Olivier used to ship his film and the only thing his envelopes said in the "captions" area was, "Same as wire service." He was as talented as he was funny. What do you recall about your time working with him?

Olivier Rebbot (center) and David Burnett on motor bike: Tehran February, 1979. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

DB: In Iran, I was often working elbow to elbow with my pal Olivier Rebbot (he of Newsweek, me of TIME) I think both of our offices would have preferred that we did not ship our film together in one packet. Those mornings would require an early trip to the airport, wandering into the departure lounge, and finding a passenger who would be willing to take your film and carry it to Paris or London or some other distant place where a TIME magazine courier would take the film, and put it in an envelope directly for New York. We had enough to do; we had enough worries without figuring out how to get our film back to New York.

One day after a number of joint shipments, one of the researchers called from the TIME office in New York and complained about the fact that we were shipping our film together with our arch rival - Newsweek. I simply invited her to come to Tehran so that she could be in charge of shipping the film and we wouldn't have that problem anymore. That seemed to have ended that discussion. Olivier was a wonderful guy, who died far too young and was really becoming a much better photographer every time he went out on a story. And that is perhaps the greatest tragedy of all that we will never know— besides the millions of jokes that we've missed — how great of a photographer he might have become.

JC: You've been the recipient of many photographic awards including World Press Photo of the Year in 1980 for a Cambodian woman with her child at a refugee camp (One of my favorite images of yours) How important are contests? With the proliferation of the number of contests as well as the number of images, have they changed in value over the years?

A Cambodian mother with her child in the Sakeo refugee camp in Thailand, November 1979. World Press Photo of the Year 1980. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

DB: I think there is certainly a value to the contests which have proliferated greatly in the last 15 years. Winning entries tend to be (not always) good work, and it remains one of the few places that, in the millions of pictures taken around the world every day, the better more compelling images can rise to the top. That said, one has to be careful not to become someone who “shoots for the contest.” There is nothing more disingenuous than work which looks like it was shot to enter into a contest. When you chase good stories, and do good work, that in itself will rise to the top.

I am somewhat suspect of those contests which demand rights by merely entering their contest, all the more so when they charge you for the pleasure of entering. It’s as if they are feeding off the hopeful egos of photographers who want to be “The One.” One of my colleagues, Ken Jarecke, has made an interesting and very valid point when it comes to those who are chosen to judge the photojournalism contests. He feels, and I agree, that editors who work for entities whose free-lance contract demands that the photographer surrender all rights to their images ought not, perhaps be the people who decide what the best in the business is. For too long we have accepted lousy terms from many magazines, wires, and newspapers, but it does our world no good to give the judging over to editors who, albeit caught in the middle, make those demands of the people they work with.

To my way of thinking, there remain a few very important contests: the Overseas Press Club (Capa and Rebbot awards), Photographer of the Year, and World Press Photo which has had some issues in the last year, but given the numbers (hundreds of thousands) of entries, it shouldn’t be surprising that some questionable pictures occasionally make it into the winners’ circle.

JC: At the 1984 Summer Olympics you captured one of the game’s most historic images of Mary Decker falling on the track after getting her feet tangled with Zola Budd. Most of the photographers were in credentialed positions near the finish line and never even saw the fall. Where were you and did you have a "Holy Shit" moment as it unfolded before you?

DB: For some reason I never got around to covering the Olympic Games until the U.S. hosted them in 1984 in Los Angeles which was odd for a guy who spent far too much time in high school and college shooting sports. In LA, which was notable for one of the great marketing screw-ups ever in photography, we assembled 5 Contact photographers, as part of the TIME magazine team of something like 15. Each Olympics until about 2008, there was a preferred photographic film sponsor - for many years it was Kodak. They had a Kodachrome lab onsite (there was nothing like 4 hour turn around Kodachrome 200!) and they ran thousands of rolls per day for the accredited photographers. Some no doubt long-gone ex exec at Kodak decided that they didn’t really NEED to be the Official sponsor of the US based Olympics, and in a millisecond, that newly (to the US market) up and coming company, FUJI, won the bid.

It was at the 1984 Olympics that hundreds of the world’s best photographers discovered the joys of shooting Fujichrome, and from that time onwards, Kodak was just a sitting duck, a target for a more aggressive company to take down. So it was that many of us were shooting Fuji films, and in particular the Fuji100 chrome film, which was very good even when pushed one or two stops. The Friday of the last week of Track and Field, when many of the big events Finals took place, I was waiting for the big event of the day. Much of that week I’d been camped near the finish line, with hundreds of other photographers, including some who had literally a dozen or more cameras rigged to shoot the action.

THE picture of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles: Mary Decker falls during the finals of the 3,000 meters. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

After several days of that, I just wanted to be somewhere else. Maybe I thought I had no chance to compete with that kind of technology. Or it was simply looking for a different perspective. I wandered down the track just past the 50 yard line, at the beginning of what was the final straight away, found a free spot on a bench, and joined a couple of other photogs who were already camped there. The big race of the week was happening soon. Mary Decker, denied a chance for Gold in Moscow due to the American boycott, had been one of the fastest long distance women runners in history, but had never run for Gold. She was running against the bare-footed South African sensation Zola Budd, a teenager who was running for the UK (her mother was English) as South Africa was still under the Apartheid boycott…and…had a full pack of great runners. Each of my friends found what they thought to be a special place for that race. One near Mary Decker’s mom (for the reaction shot) one on the far side of the track (the last bit of warm sunset light to bathe her) and yet another near the finish for the great “jube” shot.

I had no idea that I’d chosen, by chance, the perfect spot. When, half way through the race, Decker and Budd bumped into each other, and Mary fell into the infield, ending her dreams, it was merely a flash of red as seen through a flashing mirror, yielding the occasional view of what was actually happening. I swapped my short lens for the 400… took an extra second to make sure I was sharp (this was pre- Autofocus) and made a dozen frames of Mary Decker in her indescribable moment of pain and disappointment. It all comes down to being lucky, and when luck strikes, try not to mess it up.

JC: At some of the more recent Olympic games, you've been covering the events with some unconventional cameras (Speed Graphic and Holga) Tell us a little about that, including why you chose to go that route.

Sochi 2014: Ski jump training in Infrared. © 2015 David Burnett /I.O.C./Contact Press Images

DB: Near the end of the last century (how many times do you get to toss that one around?) I became impressed by the work of Eric Lindbloom in his small monograph called “Angels at the Arno.” I was impressed not only by the fact that he won two Guggenheim grants to spend time photographing sculpture in Florence (is that an amazing gig, or what?!) but that the pictures he made with his Diana camera were more beautiful than you could possibly imagine. I loved the softness, and elegance of the images, and soon bought myself a Diana to see what magic I could bring to my own Arlington, Virginia neighborhood.

I failed miserably with the Diana (to this day I claim mine was defective, though of course the designers and makers of the Diana would tell you that the “defects” were part of the charm) and instead ended up trying out a Holga. The Holga’s awkward and wonderful way of treating light led me to start carrying it on portrait jobs, newsy assignments, and sports. It required a bit of getting used to, but in its simplicity was a wonderful, elemental and simpler way of seeing. The Speed Graphic, with all its mechanical demands, also gives a different view of the same place. So, sometimes you want to be close, grab a 400, sometimes you want to show ‘what it looks like if you were standing there’ - grab the Speed, a couple of holders, and a normal lens. There are dozens of ways to see things.

JC: As someone who has experienced the analog to digital transition, how has this helped/hurt the way you shoot today?

DB: Unquestionably, there are times when convenience is a wonderful thing. You want to see the picture now? Great, shoot with the digi cam, or phone, or iPad. But not everything falls into that category of “immediate relevance.” Some things deserve a little slowing down, and a film camera will get you there. If you are really gutsy (and a lot of people think they might be, but NO ONE actually does this) put a piece of gaffer tape over the screen on your camera, and shoot like a film photographer for a day or a week. You’ll be angry, you’ll be frustrated, but if you live through it for a week, watch how much better your pictures start to become. And in the end, that is what it’s all about.

JC: And as the publishing world has become much more web based than print based, what would you like to see being done differently? What do you like? What pisses you off?

DB: I guess I still think of myself as a “magazine photographer” though most of the magazines I used to work for have altered their MO’s. From the 1960's through the next couple of decades, you had, particularly in the newsmagazine world, three things which created enormous opportunities for photographers: big budgets, lots of pages to fill and a competitive desire to beat the crap out of the opposition every week. (In my case it was mostly TIME vs. Newsweek) But the first two factors meant that editors could both entertain story suggestions FROM photographers, and have the means to send a photographer to a place where the stories were, and let the pictures be made.

Aftermath: Hurricane Katrina. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

That is perhaps the greatest thing I feel in looking back at those years when TIME and LIFE were major clients. Even if they didn’t use the pictures the week they were made, that assignment gave me a chance to MAKE the pictures, and now, 20, 30, 40 years later, I have those pictures. Almost none of the people in my era would have had the chance to travel and report (I worked in 85 countries) had there not been a healthy financial underpinning.

This brings us back to 2015. When a set of pictures which 20 years ago would have been fought over, and probably fetched $10000 or $20000 the first week it was on the market (let alone resales) and that same set of pictures today would probably fetch $500 if you were lucky, and that would include worldwide rights, and all sorts of stuff the lawyers have thought of. Of all the changes in the business, maybe that is most distressing: that a great story idea just dies because some reasonably deep-pocketed outfit decides that it ISN'T important enough to make those pictures.

I am happy to see, however that there are a lot of freelancers, mostly young who feel a need to follow a story on their own dime. Sadly, of course, you can’t keep subsidizing publishers forever. At some point, you need to be able to license your work for publication (also known as “sell some images”) and create enough wealth to at least be able to stay on the story and pay a rent check occasionally.

JC: You've had a couple of books published, do a lot of workshops and I recently had the pleasure of sharing the stage with you at a speaking engagement in Michigan. What's on the horizon for David Burnett? Are there any new books or projects in the works?

The Association of Lincoln Presenters met in Vandalia IL - the first Illinois state capital. © 2015 David Burnett/Contact Press Images

DB: Coming up, I have a book of sports photographs being published this fall (in French) and hopefully next spring in English and Chinese, called “Managing Gravity,” which is a collection of sports pictures from the last 30 years. I know I have a few other books left in me, and once “Managing Gravity” is done I hope to start wading through fifty years of photographs to move that forward. But I’m still a sucker for an assignment, and crazier the better.

Later this month, I’m going to be working with a group of friends (we call ourselves Photographers for Hope…see link below) on a project to show the renaissance and rebuilding of Newburgh, New York. In late October, I will teach a workshop in Paris at the Eyes-In-Progress, and hoping to do some other teaching in the US next year. And next summer? Well I hear there will be an election, and one helluva track meet.

JC: Lastly, what advice would you give to anyone considering a career in photography today?

DB: To be a photographer in this age, you have to really WANT to do it. Don’t do it just because you can’t think of anything else to do. Go to workshops, and perhaps more important, use your library and even the web to find work which inspires you. One of the things which I find so disconcerting is that very few young photographers today can tell you who the photojournalists of note were in the 50's, 60's, and 70's. I fear there is a certain kind of self-validation which shooting/seeing immediately engenders. It reminds me of Tom Hanks in the movie Castaway, when he exults in having made a fire. “I have made FIRE” he yells to the empty island. I think the immediacy of seeing a picture on the back of a camera convinces neophyte photographers that they really ARE something special. When in fact, their time would be spent far more profitably researching some of the greats in this business, who did everything they accomplished without the advantage of a screen on the back of their cameras.

“ In 20 or 30 years from now, the pictures which will mean something to you, and to those around you, are those everyday moments with your friends, your family, your LIFE. ”

To wit: look up John Dominis, John Zimmerman, Erich Hartmann, James Karales, George Tames, George Silk, and David Douglas Duncan, to name just a few. If you don’t know these names, then you are trying to commit to photojournalism without knowing what has been done in the world preceding you. Lastly, don’t feel you need to photograph ‘events.’ In 20 or 30 years from now, the pictures which will mean something to you, and to those around you, are those everyday moments with your friends, your family, your LIFE.

My great regret is that during high school and college, rather than take pictures of the pre-lunch poker game at the frat house, I was far too consumed with trying to be a Sports Illustrated photographer, by photographing the Colorado College varsity athletic events. I made one or two good football pictures in my four years, but all these years later, I doubt that even the guys in the pictures care much about them. The pre-lunch poker game? Now those pictures would be priceless decades later. Remember: Photograph the things, events and people in your own LIFE.

* * *

LINKS:

David Burnett Website: http://www.davidburnett.com/

David Burnett Blog: http://werejustsayin.blogspot.com/

David Burnett Workshop in Paris: http://www.eyesinprogress.com/7973/workshop-davidburnett-2015.html

Contact Press Images: http://www.contactpressimages.com/

David Burnett Book “44 days”: http://www.amazon.com/44-DAYS-REMAKING-Burnett-Hardcover/dp/B00I3O0INO/ref=asap_bc?ie=UTF8

David Burnett Book “Soul Rebel”: http://www.amazon.com/Soul-Rebel-Intimate-Portrait-Jamaica/dp/1933784261

Reporters Without Borders; 100 Photos for Freedom of the Press: http://boutique.rsf.org/products/100-photos-de-david-burnett-pour-la-liberte-de-la-presse

Photographers for Hope: http://photographersforhope.org/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/dave.burnett.16

Twitter:@davidb383

Instagram: davidb383

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

DO YOU HAVE A STORY YOU THINK IS A GOOD CANDIDATE FOR ZPHOTOJOURNAL? EMAIL YOUR SUGGESTION TO: JIM.COLTON@ZUMAPRESS.COM

Jim Colton

Editor www.zPhotoJournal.com

Editor-at-Large ZUMAPRESS.com

jim.colton@zumapress.com